Marie Antoinette’s $30 million watch (that she never lived to see it) is on display for the first time in the UK

Breguet

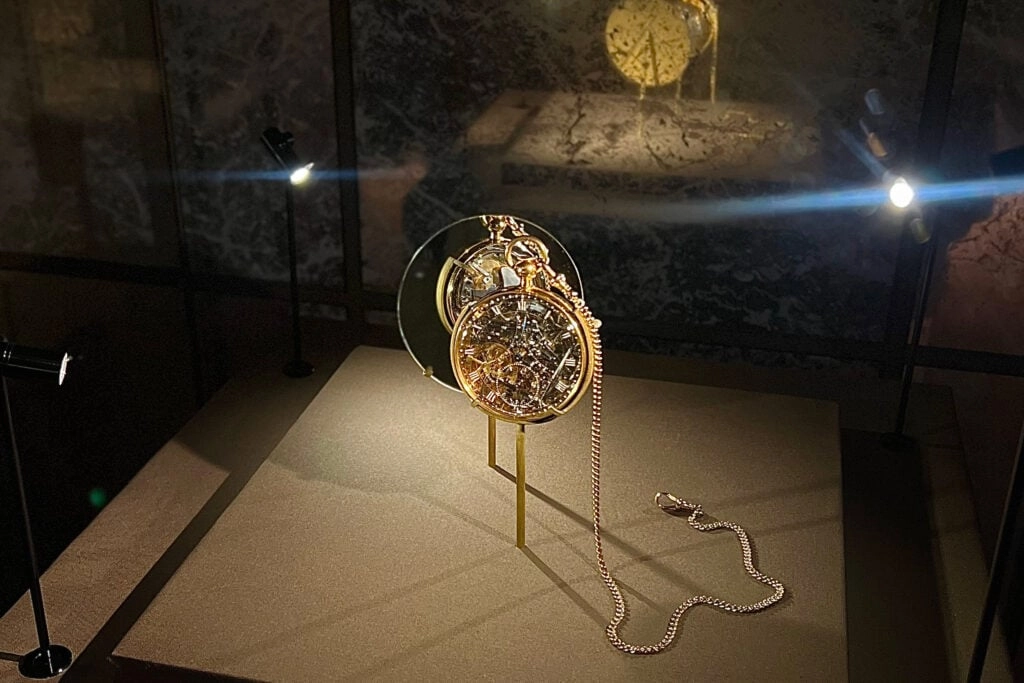

Considered one of the most expensive watches in the world, the Breguet No. 160, is a 60mm pocket watch that features a full perpetual calendar, a jumping hour hand, 23 complications and 823 parts. Known as the Marie-Antoinette, or “the Queen,” it wasn’t completed until after her death in 1827.

We dispatched an international correspondent to the London Science Museum to view the watch (marking the first time it has gone on display in the UK) and dive into its remarkable tale. This is a story that travels across four centuries, three countries, a shocking heist, an infamous revolution, and an extraordinary retrieval: this is the story of Marie Antoinette’s watch, the most famous, or perhaps infamous, watch in the world.

As it stands today, you’ll find this regal spectacle that once belonged to the French Queen nestled in the treasured halls of London’s Science Museum. Housed in the exhibition Versailles: Science and Splendour, this timely artifact has overcome so much in order to stand so elegantly in its vitrine, fascinating flocking viewers from across the globe.

Visiting the exhibition in London's South Kensington district, you’ll discover that the Palace of Versailles throughout the 17th and 18th centuries held an instrumental role in scientific innovation. From philosophy to machinery, among the developments in obstetrics, astronomy, plants and animals, water transportation and medicine, the French Royal Court was surrounded by curious thinkers and remarkable achievements.

But the origin story of Marie Antoinette’s timepiece is a blurry one. While its creator, the seminal Abraham Louis-Breguet is consolidated into the annals of history, its commissioner is not. Perhaps an admirer? A friend? The answer will never be known. But what we do know, thanks to the valiant efforts of Breguet’s archives, is that whoever commissioned it wanted to go the extra mile for the Queen. “Everywhere, gold must completely replace brass [and] all of the complications possible and known to be incorporated.”

It was, by all accounts, appointed to be the most superlative watch possible. Naturally that comes with a price, but of course, fine timepieces and royalty go hand in hand. Price is typically no issue, and so it was recorded by the unmasked client that there be “no limit on time of manufacture or on price.” A true pièce unique as we know it today.

It makes sense, therefore, that Marie Antoinette’s mystery commissioner opted for one of the most regarded names in watchmaking at the time, and to this day. A taste for technical flair, both the Queen and her husband, King Louis XVI were proud owners of multiple Breguet creations, with Antoinette even requesting a ‘simple’ Breguet watch during her imprisonment in 1792.

From the beginning, Marie Antoinette’s unique timepiece was roused in mystery, but perhaps the most mystifying detail of all was that the sovereign never saw the watch delivered due to her execution in October 1793. On top of this, Breguet was forced to flee to Switzerland four years prior, just as the French Revolution began, only to return a year before the Queen’s death, continuing his endeavors on the project for the next two decades. So when did the watch finally become complete? The watch finally landed in 1827, just three years before Breguet’s own death, under Breguet et Fils, with the help of his son.

Haute horology is, of course, no overnight feat, and the allure of such a timepiece speaks to the current of innovation that was taking place throughout the century. While showcasing Breguet’s flair for complications, what seems most exceptional about the creation was this precedent on imbuing the Queen’s watch with as many complications as possible, something that was atypical amongst women’s tastes during the period, prioritizing smaller, light-weight models.

The ‘Marie Antoinette’ perpetuelle, Breguet, No. 160, Paris, 1783-1820 © The Museum for Islamic Art, Jerusalem

Marie Antoinette’s watch is anything but that. In a mass of 823 parts, this self-winding (perpetual) watch remained true to its commissioner’s intent: a feat of mechanical excellence. Boasting Breguet’s most celebrated inventions, it contained a pare-chute shock absorber, a system to protect the balance wheel, and a forerunner to modern shock-absorbing devices today. Matched with a 48-hour power reserve, it displayed a calendar for date, day and month, accounting for leap years, an independent second hand, to enable a stopwatch function, and an equation-of-time indicator in minutes. Marie Antoinette famously enjoyed a palette of sweet delicacies, and much like the layers of a cake, her watch was layered with an entire glossary of complications. The icing on said cake was a minute repeater complication, whereby the watch could sound the hours, quarters and minutes.

Now here’s where the story takes on a life of its own. Little did the monarchy or Breguet know, this rare timekeeper would embark on a journey of its own, first leaving Breguet’s possession after completion, into the hands of the Queen’s pageboy. Following repairs in 1838 and the resulting passing of the pageboy, Breguet came into ownership once more. But it wasn’t long before the watch was touring the globe again, from collector to collector. Call it the definition of living on borrowed time, in 1917, the watch found itself in Tunbridge Wells, England in the hands of a barrister and industrialist with an affinity for all things Breguet. However, eight short years later (enough time for the owner to recognize the watch's ability to accurately surpass at least one leap year), the watch was donated to the L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art in 1974.

Living out its days to be admired by all – or so it hoped – the watch later fell victim to a large-scale heist in 1983, stolen amongst 100 other watches, nowhere to be seen for 23 years. During its hiatus from public sight, Nicolas Hayek Jr.. CEO of the Swatch Group, echoed a similar commission: tasking Breguet’s watchmakers to produce an exact replica. A tribute to Breguet’s modern-day horological mastery, this took 4 years, as opposed to more than two decades. However, two years before the replica was completed, the Museum of Islamic Art was contacted by a lawyer, who informed them about the discovery of the original watch among the possessions of a deceased collector. It was only later that the collector was revealed to be a notorious thief: Na’aman Diller.

Now, rest assured, Marie Antoinette’s uncovered timepiece appears, safely, in London’s Science Museum in all of its splendor. If you’re planning a trip to the British capital, discover it in the flesh and witness a timepiece that was not only emblematic of the immense scientific advancement under the Palace of Versailles, but a watch that defied societal norms. Given its sheer size (crafted at 63mm), and showcase of complications, it paved the way for an entire universe of complicated women’s watches. Much more than that, the spectacle of this timepiece exists not only in its form, but through the journey it has embarked upon as it awaits your gaze in its new home. To see it is to turn back the hands of time and discover the skill of our predecessors, and more importantly, to make up for lost time.

Versailles: Science and Splendour will remain at the Science Museum, London until 21 April 2025.